The Gateshead Visitor Centre, formerly St Mary’s Church, has been a place of Christian worship since the 7th Century but there has been a religious community on or near the site since the Dark Ages, with the Venerable Bede writing of monastic life in ‘Getehed’ in 653 AD.

The church has had a traumatic past, suffering occupation and bombardment during civil wars, and was situated close to the explosions and fires which devastated large areas of Gateshead & Newcastle some two centuries later. In the long and eventful history of St. Mary’s, there is one element that has precipitated major changes and that is fire. Two devastating fires, in 1854 and 1979, have shaped the building into what you see today. Victorian additions were made to the building as a result of the first fire which swept the Quayside. The 1979 fire, which was localised within St. Mary’s, destroyed the Victorian oak furniture and stained glass windows and heralded the end of St. Mary’s as a place of worship; the small congregation moved to St. Edmund’s Chapel on Gateshead High Street.

St. Mary’s Church re-opened as a working building in November 1990 when Phillips Fine Art Auctioneers bought it and turned it into an auction house. Now owned by Gateshead Council and officially known as the Gateshead Visitor Centre, St Mary’s Church is a Heritage Centre for the city.

Following the erection of an independent scaffold around the entire perimeter of the building, an in depth progressive survey was carried out by St. Astier Ltd to identify all necessary repairs. Proposals were then put forward to the Planning & Conservation Officers and other members of the Project Team for consideration.

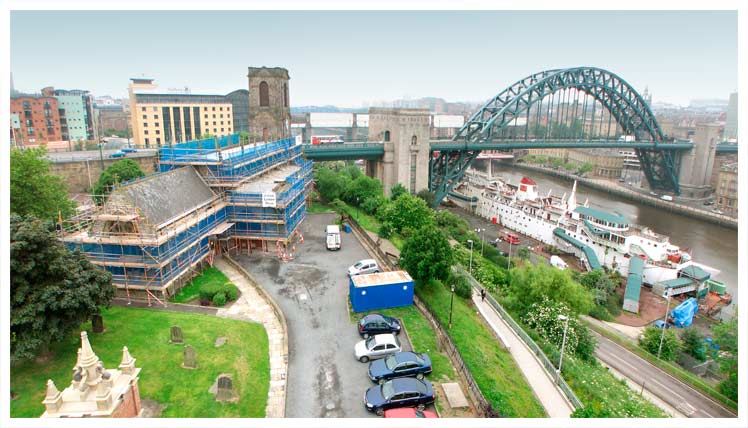

The Gateshead Visitors Centre is shrouded in scaffold to allow a through survey.

Following a period of discussion and slight amendment to the proposals, a comprehensive Schedule of Repair that addressed the conservation needs of the building was in place with the contract being delivered over a 16 week period.

A variety of work was carried out including extensive re-pointing of mortar joints on the Aisles, Nave Clerestory, Transepts and Chancel. These elevations were specifically chosen as the stone showed obvious signs of weathering to the extent at which the face had retreated to a noticeable degree. This natural occurring process had most definitely been exacerbated by previous attempts to re-point the joints between the stones with a cement based mortar mix which had been applied in an obtrusive ‘strap like’ manner in areas clearly protruding the surface of the stone.

The use of such a mortar inhibited the structures’ ability to release absorbed water leading to a build up of moisture and crystallisation of salts at the position where moisture penetrates to the cement joint. The weakening of the stone by salts and the effects of freeze/thaw action had led to the eventual detachment of the cement in areas taking with it segments of the stone face.

Whilst the work carried out has without doubt improved the general appearance of the building, the aim of the repair was not focused on aesthetical gain but moreover on protection. The use of a lime based re-pointing mortar should through its porous characteristics not only allow the structure to dry out and ‘breathe’ but should also prevent the build up of salts.

Selective indentation was also used as a method of preserving the structural integrity of the façade whilst restoring essential architectural elements such as hood mouldings, drip throatings, collars etc. and generally ensuring that water circuitry is maintained.

Evidence of previous cement based repairs and corroding iron armatures to the Tracery element of the window.

In the interests of good conservation practice which focuses on the need for minimum intervention recommendation for indentation was restricted to essential areas where such repairs should by virtue of their location assist in preventing any further deterioration of adjoining stone elements.

An eroded section of the Tracery is carefully cut back to glass line in preparation of an indentation of new sandstone

Intricate carving of stone and a minimum intervention approach was used to restore only the lost elements of the bust.

Other works included pinning of fractured sections of stone which, although in general appeared to be in relatively good condition, may have been become detached in the future. The method of carefully drilling and setting very fine 4mm stainless steel helical bars meant that the historical fabric of the building was retained and essential features were not lost.

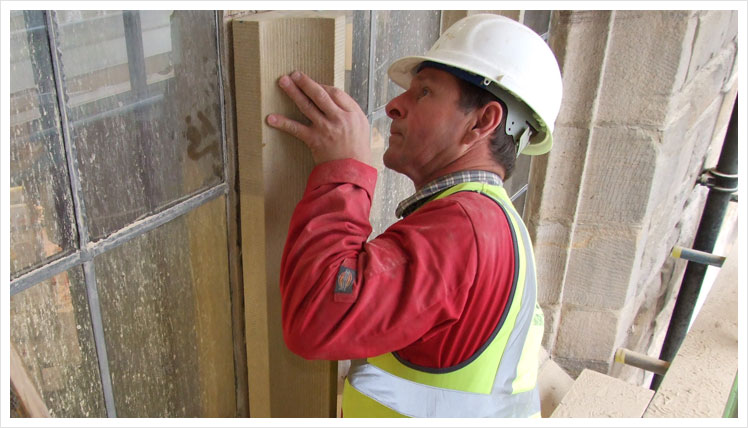

Our Stone Mason carefully aligns and lifts the replacement section of Mullion into position.

Falling under a separate contract, the roof of the nave was recovered in a metal sheet with associated works carried out by St. Astier including the cleaning of gutters, hoppers, and down pipes, and the application of leaf guards to prevent any future blockages.